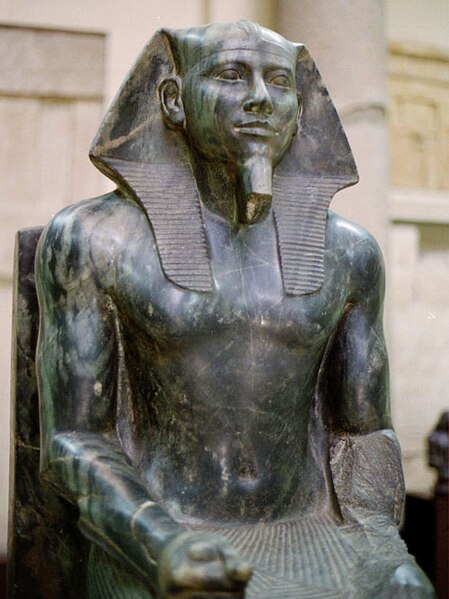

The Ancient Egyptians are most notorious for their emphasis on the afterlife and death. From Khufu in the 4000s BCE to Cleopatra in the 1st century BCE, Egypt was oriented around the brevity of life on Earth and the immortality of life in the Ka statue. The Ka was the life force of a person, the spirit that would inhabit the mortuary statue after death. Most statues were constructed for the Pharaoh or the elite; regular Egyptians could not afford the elaborate burial rituals. Another detail that hints at the importance of death was the materials that the Egyptians constructed their buildings out of. Regular structures such as houses and shops were usually made of mud brick or other cheap materials. By contrast, the important burial objects were made of limestone or expensive materials such as faience and diorite (northosite gneiss). A famous example of diorite is the Ka statue of Khafre, the builder of the second Pyramid at Giza. Diorite, an expensive medium that was incredibly difficult to carve, glowed a brilliant blue in the light, linking the Pharaoh (who was at the top of the social hierarchy) to Horus, the god of protection and the sky.

|

|

Khafre Enthroned http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Khafre_statue.jpg |

Tomb of Perneb, Metropolitan Museum, NYC

Next, the Etruscan civilization of Ancient Italy also valued the afterlife above earthly matters. Eretria was a wealthy region in central Italy, and it prospered from the 11th to the 1st century BCE because of the valuable metals mined there (i.e. copper, iron, and tin). Although no Etruscan temple survives completely intact, models show that the temples were similar to the Greek temples before them. The Etruscan temples had red columns (from Minoan civilization?), a pediment without sculptures in it, non-fluted doric columns that tapered at the end, a prominent portico (porch), and three cellas. The medium was stone, which contrasted to the ordinary building materials of wood, mud, and brick.

Tomb from Cerveteri, Italy

|

|

Etruscan Wall Painting http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tomb_of_the_Leopards |

Gotland Memorial Picture Stone

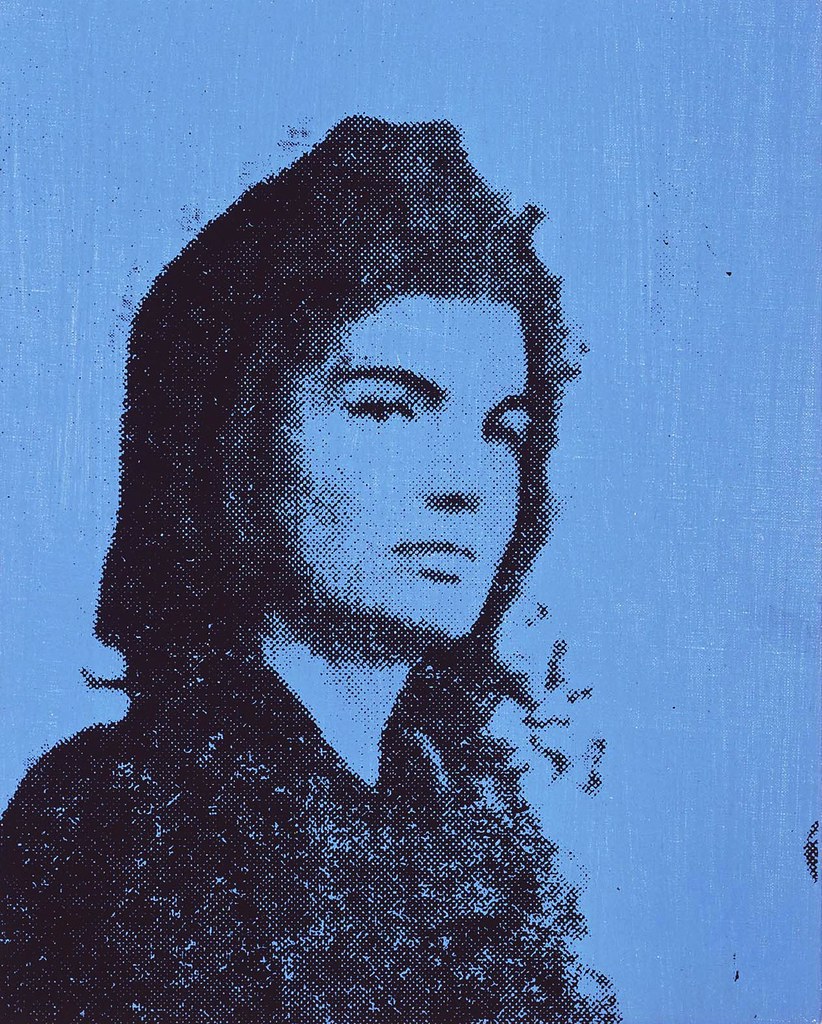

Finally, Andy Warhol and his Factory cult were obsessed with death in the 1960s. After he was shot in 1968 by feminist Valeria Solanas, Warhol’s art became increasingly oriented towards death. He started silk-screening disturbing images such as electric chairs, car crashes, and gaunt skulls; all were memento-mori’s referring to his near brush with death. However, Warhol’s images, while still poignant, have been altered by mass media and the commercialization of art during the 1960s. The pictures are grainy and separate the viewer from the real emotion of the scene (much like seeing emotions depicted in comic strips). The viewer sees, but does not feel the horror that that images are truly conveying. This reflected Warhol’s statement that mass media was the future, and the only way for everyone to get their “15 minutes of fame.” Thus, death was also reduced to a spectacle reported on by newscasters looking to make a profit on the story. Warhol was all about glamour and fatality only added to the mysterious nature of his image and the Factory. The Velvet Underground, Warhol’s band, even sang about overdosing because of Heroin, the drug he associated with the glittering, ephemeral world of celebrities. Sadly, Andy died because of complications during a gall bladder surgery in 1987 in New York City. Just for a fun fact, Andy Warhol’s real name was Andy Warhola, but he dropped the “a” to make his name sound more chic.

|

http://www.flickr.com/photos/goincase/8369055044/ Jackie Kennedy after the death of her husband http://www.flickr.com/photos/98701585@N02/9415965524/ |

No comments:

Post a Comment