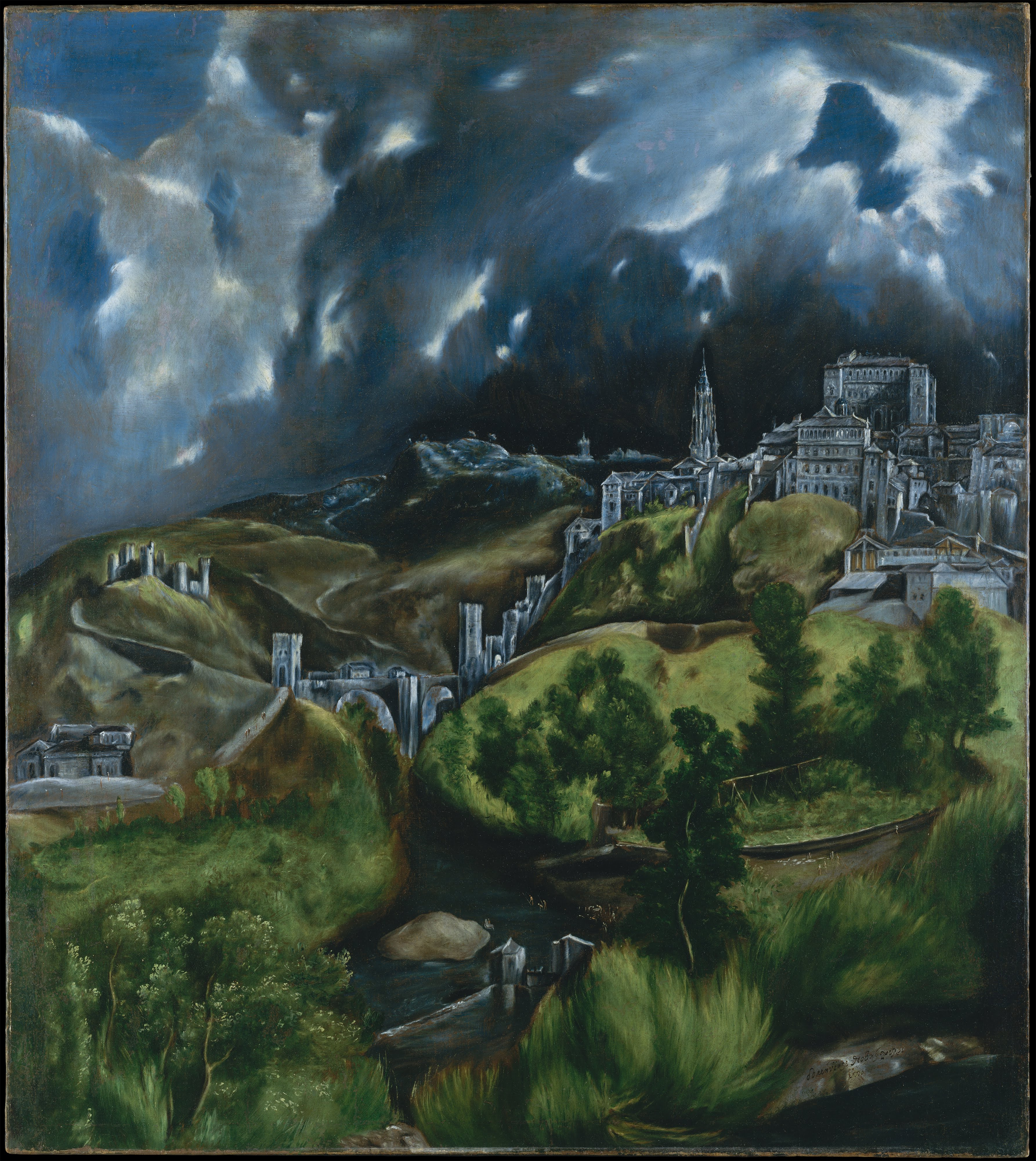

This oil on canvas in the National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C.) was painted by El Greco in the beginning of the 17th century. El Greco (1541-1614) was born in Crete, a small Greek island near the Cycladic islands in the Aegean Sea. The Minoan culture flourished there during the Bronze Age, and palaces such as Knosses were labyrinthine, centered around an open court, and built out of wood to withstand the numerous earthquakes. Already coming from a solid artistic past, El Greco was trained as an icon painter (icons are holy images of Mary or Jesus) in the early years of his life. Like so many other great “masters” who were not native to Italy, El Greco (literally “The Greek”) made a pilgrimage to that country in 1567 to observe the new prolific art styles. A few decades earlier, Michelangelo had been painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel and Raphael was being an artistic boss in the Vatican Signature Room. Because his real name (Doménikos Theotokópoulos) was too difficult to pronounce, the name of “El Greco” caught on quickly. El Greco trained under Venetian artists during the second stage of his career. He was undoubtedly influenced by the ghostly lighting of Tintoretto and the masterful treatment of color and modeling that is synonymous of Titian. He moved to Rome in 1570 but finally settled in Spain in 1577. Spain was also undergoing its “Golden Age,” although the Baroque age characteristic of the middle 1600s was still developing (i.e. see my video on Velázquez’s early paintings here.) El Greco spent the rest of his illustrious career in Toledo, an ancient town famous for harboring three different yet coexisting religious (Christianity, Judaism, and Islam). It was in this rustic Spanish town that El Greco painted this image in the last years of his life.

Laocoon and Sons, Vatican

Laocoon is a striking painting, and it is the archetype for the advanced style developed by El Greco throughout his career. The story of Laocoon comes from Virgil’s Aeneid, and it describes that of a Trojan priest who was murdered (as well as his sons). Laocoon warned the Trojans against accepting the fabled “Horse,” but the Trojans disregarded his crazed remarks after Poseidon sent snakes from the sea to strangle him (Poseidon was on the side of the Greeks). This image depicts the most poignant moment in the horrific yet fascinating tale. The snakes have risen up, the distorted and muscular body of Laocoon is powerless on the ground (with a grinning snake about to bite his face), and one of the sons is gracefully wrestling with another menacing reptile. Let’s discuss the figures first: the twisting, overly muscular, and ghostly bodies are characteristic of El Greco and Mannerism, a sophisticated art style that emerged just after the High Renaissance. After the virtuosity of Michelangelo and the beauty produced by Titian, where else were European artists supposed to turn? The next generation cashed in on Mannerism, a style that featured bright colors, no sense of a solid ground, awkward poses, elongated bodies, and radical perspective. El Greco was the pioneer of this movement, and his stormy blue/gray skies, forlorn expressions on his figures, and impossible body shapes make this priceless work unforgettable. El Greco borrowed the chaotic bodies from a Hellenistic sculpture ("Laocoon and Sons") created by Athenodoros of Rhodes, Polydorus of Rhodes, Agesander of Rhodes. The sculpture is currently in the Vatican museum in Rome. The expression on El Greco’s Laocoon is incredible; he is looking up in grim acceptance of his fate, and almost seems to adopt a Christ-like expression (although this is a pagan myth). As compliments to the dark lighting, the bodies are ashen and bruised looking (El Greco used dark blue as muscular shading.)

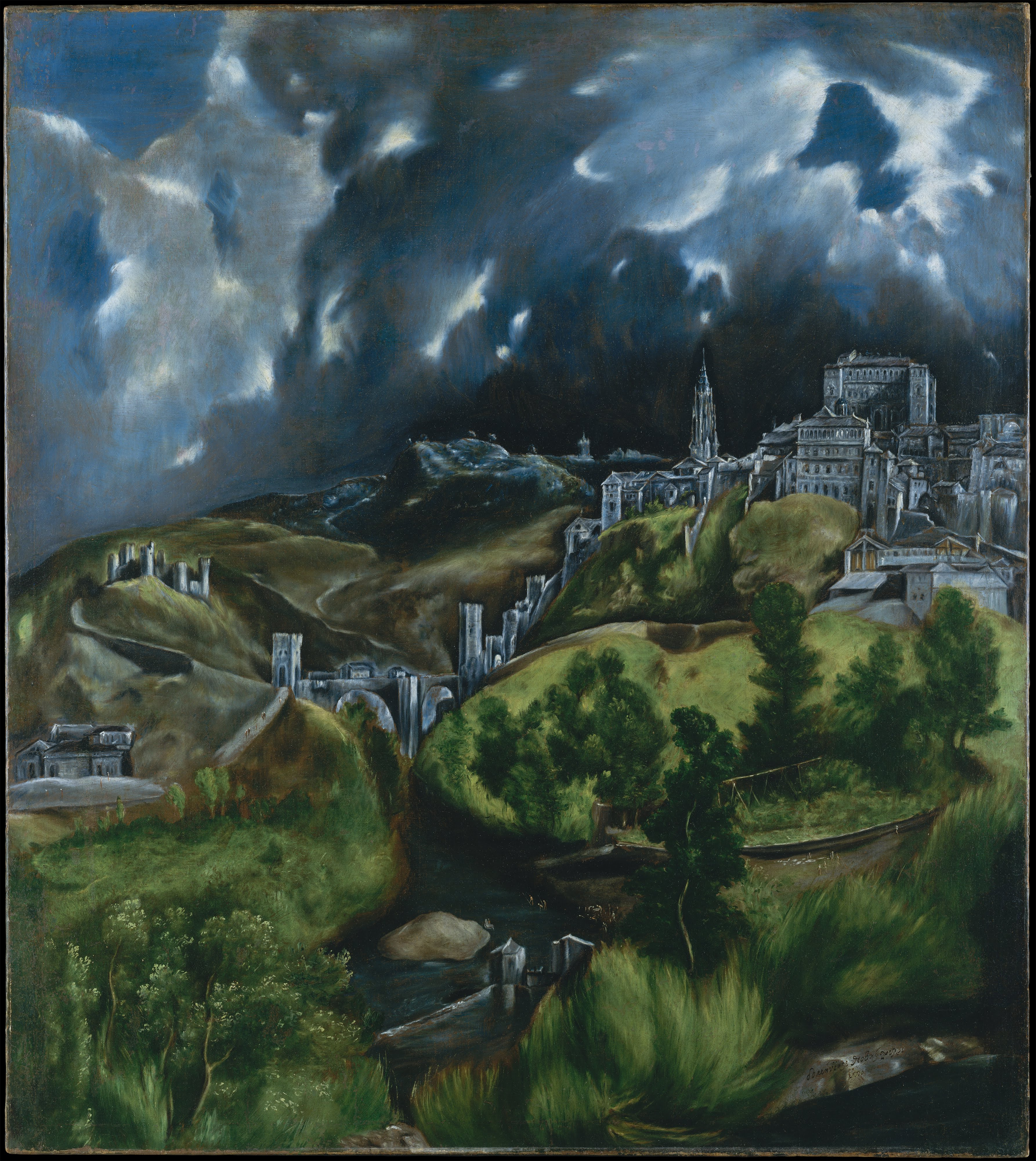

View of Toledo

The ethereal scene is brought down to Earth by the town in the background. Although the city would have been Troy according to the Greek legend, the city depicted by El Greco is Toledo, his beloved home. The notorious Trojan Horse is shown as a haunting shadow as well as ancient bridges that are actually present in Toledo (i.e. Puente San Martin). Most of El Greco’s paintings feature Toledo as a background, but the figures in the foreground are the center of attention (as opposed to View of Toledo). As for the composition, there is a lack of perfectly straight lines; the bodies and even the city are undulating and curvy. This turbulent composition only serves to heighten the emotional overtones in the image; these men are dying a brutal death. This work is stunning and monumental, especially as it was one of the only non-religious works that El Greco ever completed.

El Greco clouds