What do these two dissimilar objects have in common?

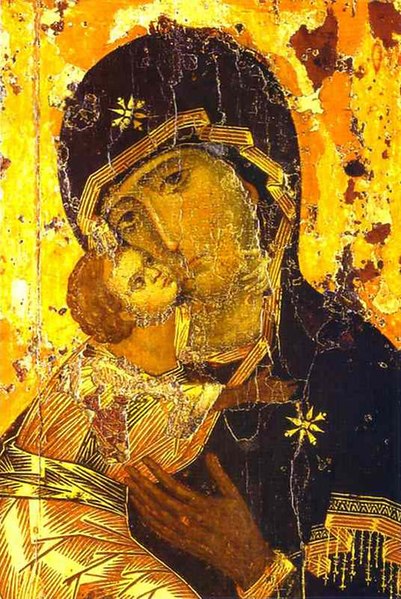

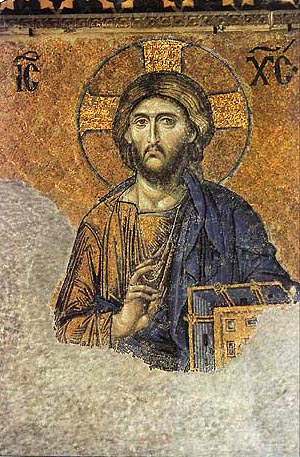

How does a faceless worker on a neon construction sign relate to a frozen image of Mary as the Theotokos (Bearer of God)? It is the idea behind the entities, not the visible aspect that is the connecting link.

Street signs are everywhere: crossing signs, construction warnings on the interstate, caution signs—they’re omnipresent in our everyday lives (at least in the developing world). These images are composed of geometric shapes: the basic circle, square, triangle, and rectangle. But why do the people on the signs not have faces and are completely unrealistic looking? 86% of adults in the United States are literate (32 million adults still cannot read), so it’s not like the average American couldn't process a sign with more complex, realistic imagery. However, the basic and most simple form in the easiest to understand, and our brains are wired to compute the most mundane/simple images the fastest. It’s the idea behind the triangular mother leader her square-headed child on a sign in front of an elementary school crosswalk that matters. One doesn't normally question, “Why doesn't the couple have eyes or a mouth?”

How does a faceless worker on a neon construction sign relate to a frozen image of Mary as the Theotokos (Bearer of God)? It is the idea behind the entities, not the visible aspect that is the connecting link.

Street signs are everywhere: crossing signs, construction warnings on the interstate, caution signs—they’re omnipresent in our everyday lives (at least in the developing world). These images are composed of geometric shapes: the basic circle, square, triangle, and rectangle. But why do the people on the signs not have faces and are completely unrealistic looking? 86% of adults in the United States are literate (32 million adults still cannot read), so it’s not like the average American couldn't process a sign with more complex, realistic imagery. However, the basic and most simple form in the easiest to understand, and our brains are wired to compute the most mundane/simple images the fastest. It’s the idea behind the triangular mother leader her square-headed child on a sign in front of an elementary school crosswalk that matters. One doesn't normally question, “Why doesn't the couple have eyes or a mouth?”

The idea behind the image, that of a transcendent universe containing the divine, comforted and inspired the masses. The realistic ways of the ancient Greeks and Romans had been forgotten with the demise of the Roman Empire in 476 CE (the last Western Emperor was Romulus Augustulus). With the dawn of Justinian and God as an entity to be feared, reality was substituted for the divine. However, the common man wasn't aware that reality could be depicted naturally; learning in Europe ceased and the few learned souls were cloistered in self-sustaining monasteries (i.e. Cluny Monastery). Learning was being faithfully preserved in the Mosques of the Umayyad and Abbasid dynasties in the Middle East, but European Christians wouldn't have access to that knowledge until the Crusades.

To wrap up, how are street signs and religious icons similar/different? Both are a visual stand-ins for a broader idea (safety in today’s culture versus religious intensity in the Byzantine Empire).

To wrap up, how are street signs and religious icons similar/different? Both are a visual stand-ins for a broader idea (safety in today’s culture versus religious intensity in the Byzantine Empire).

No comments:

Post a Comment