Mackenzie Patel

The thick, slightly musty, and fine print pages, stacked together so densely and perfectly, contained more information about Russian agriculture, turbulent love affairs, musings on peasants, and frivolities of the 19th century upper class than I thought I’d ever need. Of course, I’m referring to the literary beast that is Anna Karenina. To be honest, I only started reading this book because everyone else on my academic team had already read it or was planning to devour it’s nearly 1,000 pages. Like the tumultuous Russian composers, I find Russian authors, notably Nabokov and Dostoyevsky, completely spell-binding, their written emotions and depressing plots more intricate than the Minotaur’s maze. I barely knew that Anna Karenina had been made into a film starring Keira Knightly, let alone how deeply involved and violently emotional the story was. I still have 300 pages to go, yet the compelling nature and utter brilliance of Tolstoy’s literature has already sunk its addictive knife into me. While reading this mammoth novel, I had specific ideas of what each character, meek or brazen, sinister or ignorant, would look like in real life—except for Anna of course, who I imagined purely as the dashing Keira. Here are a few portraits, by famous and obscure artists alike, whose subjects perfectly match my fantasy renditions of the multi-faceted Russian characters.

Vronsky

This sleek womanizer, while undoubtedly debonair and charming enough to lure a married, successful woman away from her high life of comfort, always seemed rather feminine to me. Yes, Vronsky was a brilliant officer in the Russian military, could shoot snipe in a wild marsh in Siberia, and fail spectacularly at horse racing, but he also meticulously picked out his aristocratic outfits and cared immensely about what others thought of him. The love story behind him and Anna, while definitely tempestuous, was so pathetic and desperate to me. Their love was born of hasty lust, and it ripped them to shreds more than it added to their characters. Even after fathering an illegitimate child with Anna, Vronsky was easily annoyed with Anna; he was so blind to her desperation that he begrudging placated her with a caress or stare while secretly lamenting the loss of his freedom. an oil painting completed by Salvator Rosa in 1649, is the Spanish reincarnation of the suave Russian babe. The figure’s rushing, brown locks, the brooding look settled on his distinguished features, and the sense of guilty urgency wafting about him practically scream Vronsky. This painting is currently in the stunning Ringling Museum of Art; read an earlier post about the Ringling here!

Karenin

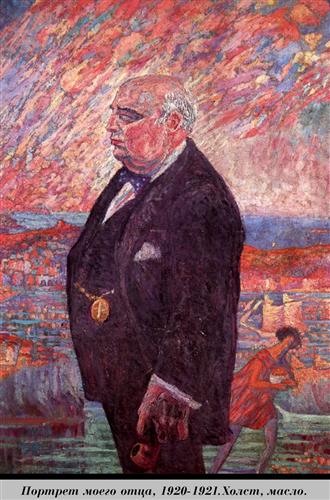

http://www.wikiart.org/en/salvador-dali/portrait-of-my-father-1921

While I find Vronsky too sexy and childish for his own good, I utterly loathe Karenin and every word he speaks, every thought that pops into his fat head, and every action he does so mockingly and selfishly. The older, stiffer, and not entirely human husband of Anna does everything in his power to stifle the bewitching spirit of his unfortunate wife. A rule-abiding official that only married the young Anna out of obligation, this toad of a man crushed her enchanting nature into a messy pulp of desperation and shame. Once he discovered the rapturous affair between Anna and Vronsky, his behavior became more disgusting still—he chose to forgive the damned couple only to feel “holy” and “religious” for himself, not because of pure altruism! His hypocrisy was a thousand times dirtier than Vronsky’s petty and boyish thoughts, for Karenin openly acknowledged that he was ruining his wife—and he relished in her pain. Because Karenin was so much older than Anna, I imagined him as the austere and heavy set father of Dali in an unflattering portrait dating from 1920. Dali’s father was also an official figure (a notary) and his unattractive features, unseeing stare, and concern for propriety mirror Karenin’s character.

Levin

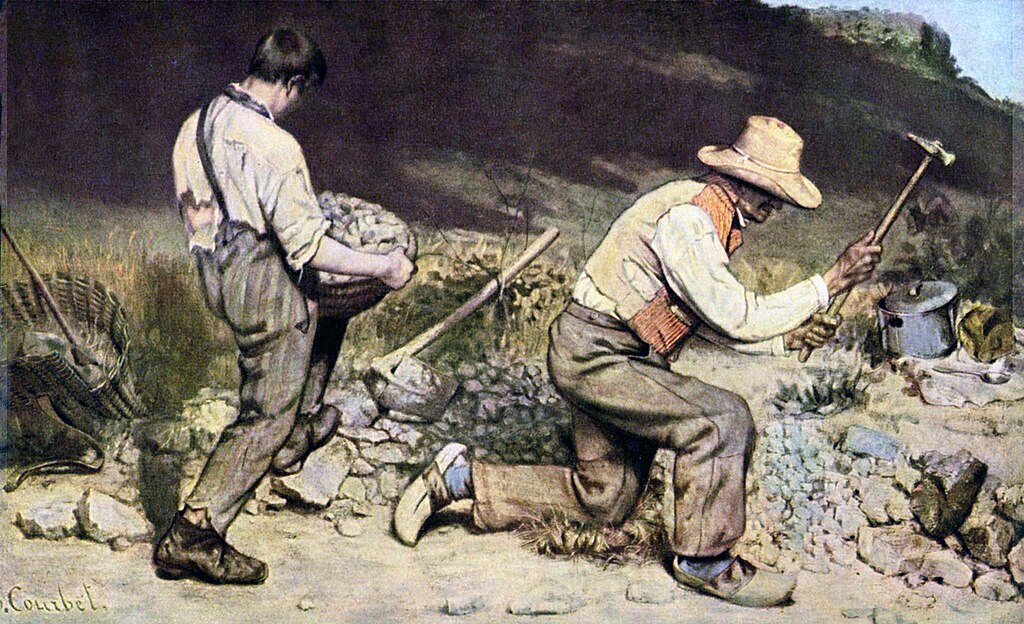

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Stone_Breakers

This brutish young man, embarrassed in front of women, caught up in passionate frenzies when his carnal emotions carried him away, and way too obsessed with Russian peasants, was nonetheless one of my favorite characters. Despite the fact that he was an aristocrat, he sympathized with his poor farm workers, truly appreciated the beauty of his countryside, and could see straight through the glitzy, empty, and repelling farce that was Russian High Society. Though others deemed his manners crude and vile, I found them charming, and his purity of thoughts was refreshing (compared to Oblonsky, who cheated with every maidservant he could lay his gloved hands on). He loved his wife and his farm, his brothers and his peasants. He was the absolute antithesis to every other selfish, indifferent, and rich character of the novel, especially his pathetic wife. Although the rough man’s face is concealed, I clearly see Levin as the older peasant in The Stone Breakers, a French realist painting created by Gustave Courbet in 1849. Everything, from the earthy tones of the image to the straining of concealed muscles, screams labor and hard work. The stones scattered around the grim man, the upraised hammer that compositionally mirrors the young boy to the left, and the tin pots strewn about evoke pity for these damned laborers.

Kitty

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Swing_(painting)

I’m pretty sure if Kitty got any frillier or pathetic, she’d turn into a soiled doily. This spoiled young girl, who was first in raptures with Vronsky and rudely disregarded the wholesome Levin, went into depression for over a year because the effeminate officer did not love her back. Her lack of grit and backbone was repulsive; she was dramatic about everything and yet failed to realize just how lucky she was! Peasants were groveling for food around her, breaking their backs sowing, plowing, or picking, while the biggest problem on her ceramic plate was what dress to wear to the evening theater. She was the most selfish character in the book, second only to Karenin (who was a decked out robot rather than a human being). Kitty was the literary personification of Rococo art, her upper class nature and unconcerned frivolity completely opposite to Levin’s realistic and wise qualities. Specifically, Kitty is a dead match for the syrupy ocean of pink and cream that dominates The Swing, an image painted in 1767 by Fragonard. In essence, Rococo art depicted the meaningless exploits of the upper class, their elite indifference ultimately provoking the bloody French Revolution.

Serezha

http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/museums/la-et-cm-lacma-new-objectivity-german-art-review-20151005-column.html

At first, I wasn’t the most enthusiastic fan of Serezha, Anna and Karenin’s firstborn son. He was a scared, timid little boy that latched onto his mother in the beginning, slowly maturing once the full blown drama of the scandalous love affair exploded around him. He was spoiled, entitled, and confused, but also pitiful when his father and Lydia Ivanovna heaped lie upon lie on his fair features. The Countess Ivanovna was a powdered snake that ruined the boy’s psychological development in a perverted, Freudian manner. For example, “The Countess went to Serezha’s part of the house and there, watering the frightened boy’s cheeks with her tears, told him that his father was a saint and that his mother was dead.” (Part five, chapter 23). What a lying, high class tramp! However, the love between Anna and Serezha was so beautiful and pure, especially when they were reunited on Serezha’ birthday. An untrusting, pallid face, expensive, muted clothes, and icy eyes construct themselves into the figural representation of Serezha in Kurt Günther’s Portrait of a Boy from 1928. The Weimer look of indifferent austerity is evident, and I imagine Serezha would be just as heavily jaded, what with all the lies, the horridness of his father, and the rapid disappearance his mother. There’s something so cold and impenetrable about this portrait; he doesn’t resemble a little boy, rather a cynical adult that only sees the world in shades of black and grey.

Anna

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portrait_of_Adele_Bloch-Bauer_I

Even though the gorgeous image of Keira Knightly pops into my head whenever Anna is penned into a scene, she still deserves a regal, stunning, and brilliant portrait from the annals of art history. She IS the personification of Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer by Gustave Klimt, especially the raven hair, the mystical quality shrouding her dainty face, and the aura of pure gold that surrounds her. The tragic event in Anna Karenina, besides the eventual suicide of the heroin, was the extinction of that vitality that defined Anna from the beginning. Her forceful nature, her quick grace, her quiet but powerful confidence—all was extinguished once Vronsky wrecked her life with desire and Karenin with his bitter revenge. She was so beautiful and alive, but every last dancing flame ultimately suffered from severed legs.