Mackenzie Patel

Hello World Travelers! This was the month of Tolstoy, the month of declaring I was going to party hard and then staying home every weekend, and the month of discovering the amazing qualities of black leggings. Second semester of college high-fived me with an amiable “welcome home!” combined with “your classes are actually difficult this term.” Cold weather bit my hands and lips and snow flurries melted onto my Gap Kids peacoat. I graduated to Mozart on my flute and donned an ill-fitting suit for Career Showcase. Overall, this month was stellarly unremarkable in terms of major life events, but I may have begun a life-consuming, potential-ridden, and eye-draining writing project…

Literature

- Beloved Friend: The Story of Tchaikovsky by Catherine Bowen and Barbara Von Meck

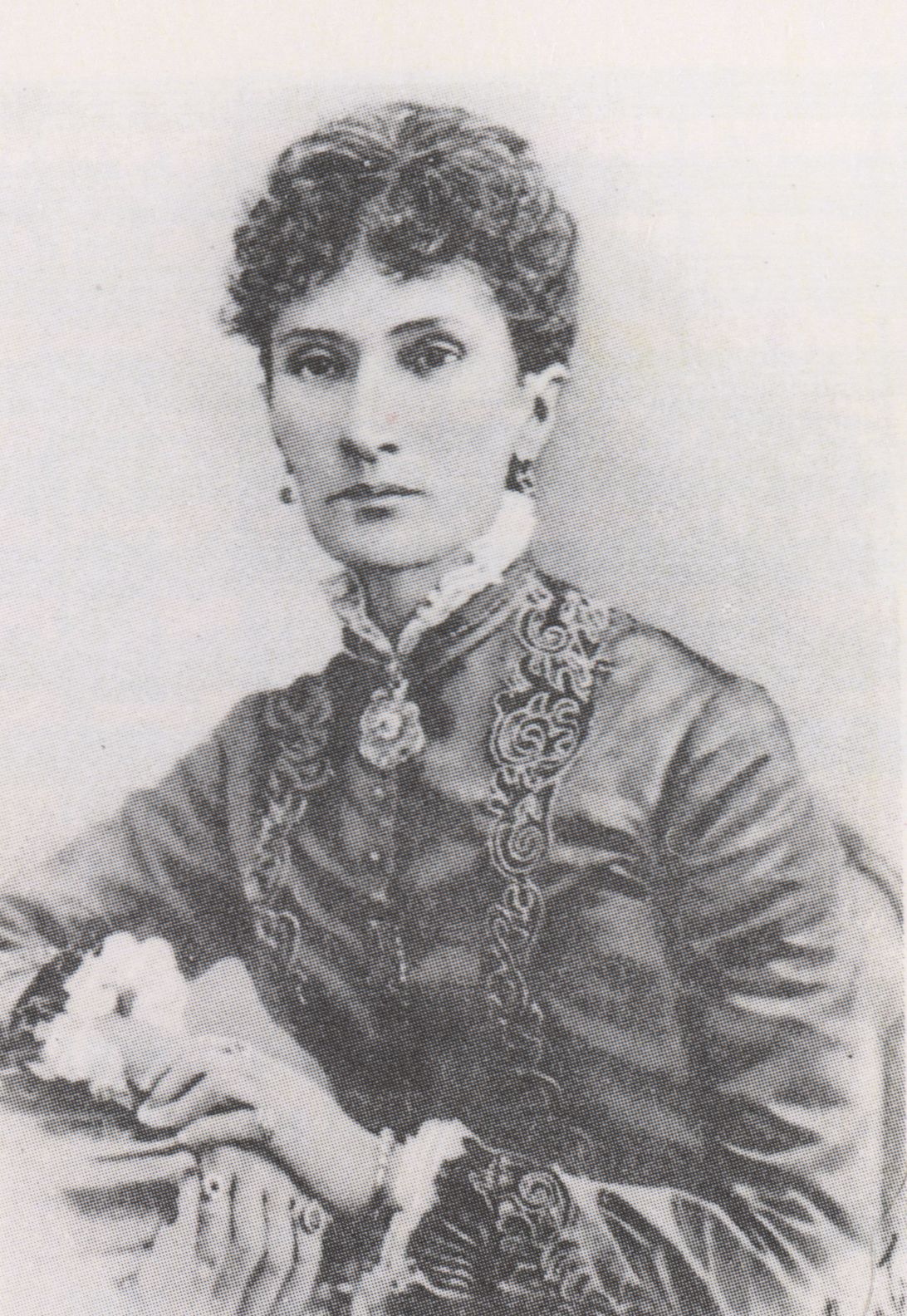

Nadezhda Von Meck

This fascinating read is technically a biography, although its thin and musty pages are infused with a unique literary twist. The letters of Tchaikovsky to his elder benefactress (Nadejda Von Meck)—and her emphatic responses—are splashed across the pages dramatically, his emotions and strange personality revealed in a sometimes unflattering way. Barbara Von Meck, Nadeja’s grandson’s wife, inherited these priceless letters and helped compile them into a riveting, insightful tale of lust, life, and quarter notes. Tchaik loathed human interaction and had a genuine fear of speaking with enemies and friends alike. I am convinced his anti-social tendencies stem from him being gay in a traditional (and oppressive) Russian environment. He foolishly married the ninny Antonina to quash his homosexual tendencies, but ended up spiraling down the nauseous path of mania. Despite his personal flaws, his music is still pure perfection and grips my heart with projected emotion—when I hear his theatrical notes, I am alarmingly alive and feel as if I were treading on a carpet of fire.

- Childhood, Boyhood, Youth by Tolstoy

Since I am enrolled in a War and Peace class at my University, we read this trilogy to prep for the Russian beast I start today. This intricate work was published in 1852, although its themes and universal appeal to young people still stamp its yellowing pages with relevance. A fictionalized autobiography, this book tells the story of Nikolai Irtenyeff, a Russian aristocrat struggling with the thorny rosebush that is growing up. The three categories—childhood, boyhood, and youth—were depicted so fully and minutely that despite the 164 year age difference, I find myself enraptured with the relatable story. I do not own surfs or plan on getting married at age 18, but the struggles with identity, first loves, and burgeoning independence I know only too well. The main character was whiny and arrogant, but key scenes (i.e. death of his beloved mother, the hilarious ball room disaster, and the symbolic carriage journey) were eloquently written.

- Sevastopol Sketches by Tolstoy

Crimean War Depiction

In contrast to the lighthearted, domestic work described above, this trilogy assumed a darker and gorier vibe. Tolstoy fought in the bloody Crimean War from 1854-55, and his account of that 19th century Vietnam, although its accuracy may be doused with doubt, was shocking and stark. Severed limbs and whizzing bombs and manly ego claimed the pages with gusto. Tolstoy’s use of the pronoun “you” I found invasive and a direct assault on the clear window between the reader and fictional characters. I was literally pulled into the story, each cannon ball nearly missing my face and my nose filled with the stench of the dead with every passing paragraph. It was a gruesome and psychological depiction of war time, for every man—whether aristocrat or mere infantryman—was always thinking “better him than me.”

Music

“Music…that longing for something mysterious, inexplicable, and at the same time marvelous, intoxicating—one would like to die experiencing it.”

–Tchaikovsky

- Serenade for Strings in C Major by Tchaikovsky

It would be the ultimate pleasure for all of Tchaikovsky’s music to be transcribed into touch, taste, sight, and smell, so I could gorge on its beauty and forever be sated. Alas, my ears receive the treat once again, for this composition is heart-breakingly sad and beautiful. There’s something about a pure string section filled with a delicious melody and voluminous crescendos that appeals so strongly to me. The cellos anchor the deep sea, the violins are the waves white with foam, and the basses transform into solid rocks sprinkling the sandy floor. This 1880 piece reminds of Adagio for Strings (Barber), but the cold string raindrops of Tchaik are fuller, happier, and tinged with sunlight.

- Symphony No. 4, Second Movement by Tchaikovsky

Again, this Russian genius is overlord and savior of orchestral string music. The deliberate slowness, plump with passion and uncommunicable angst, is astonishing. A veil of darkness surrounds me, caresses me, whispers sadness into my ears, and yet I can’t close out of the YouTube recording. Tchaikovsky wrote this piece at the onset of his feverish friendship with Madame Von Meck—he even referred to it as “Our Symphony” in his letters to her. Lying in the darkness on my bed, with no light visible except the fireworks in my brain, and listening to these ethereal nine minutes is Clockwork Orange-esque, but no less satisfying. He penned this beauty in 1878 and wrote to Von Meck,

“Never before has any orchestral composition cost me such labor, but never before have I loved any work so much….I think this symphony is something out of the ordinary, the best thing I have done up to now. I am very happy that it is yours…”

- Symphony No. 40 in G Minor by W.A. Mozart

Ever since the Magic Flute obsession, a certain fondness for Mozart has plagued me. His works are frilly, compositionally perfect, and hackneyed, but his classical charm and ubiquitous giant wig enchant me. I have officially graduated from my amusing Handel flute Sonatas to a full blown Mozart flute concerto—and it is flawless! My playing absolutely butchers the piece, but the feelings of drama and innovation tickle me with excitement. Symphony No. 40 is immediately recognizable as a piece you’ve heard a thousand and one times, but never knew the name of. The strings are playful to the hilt, although a sense of dark urgency tinges the lace as well.

Images of thick impasto and layer upon meticulous layer of Baroque oils have unfortunately eluded me this month, and I do not have many art favorites. Music and literature have elbowed this segment temporarily out the way, asserting their dominant squiggles over my culture radar. But have no fear! A few images have been lurking in this visual mind of mine.

- The Sea of Ice by C.D. Friedrich

The Sea of Ice

I’ve written about this romantic stud before, but this tour-de-force of unbridled nature is a new level of talent for his skilled hand. Painted in 1823, this large canvas depicts a staggering phenomenon, although whether a jagged finger of ice could naturally assume this precarious stance is questionable. Its icy blueness pierces the sky, the miniscule boat lying pathetically on its side in the wake of this Arctic beast. This work hangs in the Kunsthalle Museum in Hamburg, Germany, Friedrich’s more famous A Wanderer Above A Sea Of Fog claiming the spotlight on the adjacent lilac wall.

- Salvador Dali Vs. Star Wars by Juan Cairos

https://www.tumblr.com/search/salvador%20dali%20artwork

Uniting two of my favorite icons, this kitschy fan art is nonetheless studded with badass pizazz. The AT-AT drivers of the evil Empire roam the Dalinian landscape of sickly yellows and pale blues, the golden death star looming in the sky. Cairos was directly referencing The Temptation of Saint Anthony, a trippy oil on canvas that Dali painted in 1946. Although containing elephant-like creatures, this work is a risqué version of Star Wars, with bizarre images of female breasts, buck-teeth horses, and ruinous temples imprisoning more naked bodies…

I hope everyone had a month more wildly adventurous than mine! See you here next month. ;)