Mackenzie Patel

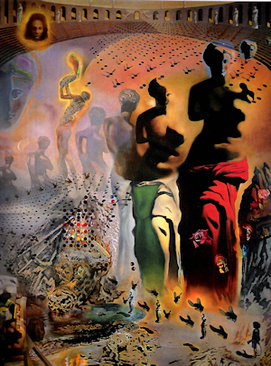

Stately nudes inhabiting the kaleidoscopic bullring. Flies swarming about the place like darts of coal. A dwarf-like boy anchoring the right side of the canvas with a sailor cap and hoop. Of course, the painting I am referring to is “The Hallucinogenic Toreador” that was painted by the eclectic Salvador Dali from 1969 to 1970. Dali was around 66 years old by the time he produced this massive canvas of 157 by 118 inches (one of the last large scale works he would ever complete). Dali abandoned monumental works because he was devoting his time and energy to building his grand museum and mausoleum in Figueres, Spain (his Catalan hometown). Having visited his singular museum in the summer of 2013, I completely understand why it took so much effort and dedication to construct it—it’s extremely strange, detailed, and like walking in a paralyzing daydream through the intricate (and sexual) mind of Dali himself. Just like that museum summed up his fascinations and lifetime obsessions, The Hallucinogenic Toreador contain symbols and imagery from his early art periods. Mashing together surrealism (i.e. the many figures from Millet’s The Angelus painting) with nuclear mysticism (i.e. the dissolving flies), this large scale canvas is all over the place stylistically and chronologically. I am particularly enamored with this painting because it contains a poignant double image of two very interesting and disparate characters: Venus de Milo and Manolete. The archetype of Western beauty and ideality, the no-armed Venus is a Hellenistic statue from ancient Greece. Within her multiple forms (there are 31 Venus’ in total) is hidden a double image containing the face of Manolete, a famous bullfighter from Spain.

Born in Cordoba on July 4th, 1917, Manuel Laureano Rodriguez Sanchez (Manolete) came from a family of notable bullfighters; however, he was destined to become the most beloved bullfighter of all in the 20th century. Alas, his story ended in tragically in his thirtieth year when he was gored to death by a feisty bull. His haunting look, drawn face, and majestically melancholy stance was so piercing that I researched the famed Manolete a bit further. It turns out this hometown hero initially disdained bullfighting; his sickly demeanor as a child certainly did not suggest bravery or heroism. However, he performed and killed with “style and taste,” and was able to execute moves smoothly and demurely. He performed all over Spain (i.e. Seville and Madrid) and even thrilled the bloodthirsty masses in Mexico and other South American countries such as Peru and Venezuela. Barnaby Conrad, author of The Death of Manolete stated perfectly that “he [Manolete] was the embodiment of everything Spanish.” He finally met his end in Linares, Spain when he was gored to death by Islero the bull (1947); the solemn-faced legend was only thirty years old. His last words were purportedly “Doctor, are my eyes open? I can’t see!” If you’re going to kick the bucket, might as well be as dramatic as possible. The whole of Spain reeled—their most beloved fighter had been ripped apart in the groin and finally laid to rest in Cordoba, his birthplace. I find the life of Manolete so fascinating because I actually saw a rather bloody bullfight in Madrid a few years ago. Read about my experience here.

Dali included the tragic Spanish martyr in his painting to emphasize the overt theme of unrequited love. Venus, although she is the height of sensual grace in the Western world, is unable to help or protect Manolete from dying because she has no arms. Going off this theme of turbulent love, Dali also included small images of himself as a child (lower right corner) and Gala, his wife (upper left corner). Their diagonal gazes, so direct yet so far away, reflect their rocky relationship at the time this canvas was painted. Gala, around 76 years old, was living at a castle in Púbol by herself; in order for Dali to visit her, he had to write a note asking for permission! Gala also disapproved of bullfights, which explains the sour look slapped over her complexion. Despite her disdain of fighting, Dali included the double image of a bullfighter raising his cape to Gala inside the shadows of a lingering Venus under her.

Since this image was a culmination of his entire painting career, it contains multiple symbols that first appeared in his earlier art periods. For example, the flies zooming around the canvas in parallel lines go back to his nuclear mystical phase in which objects were depicted as disintegrating atoms. The flies are also intertwined with a local Catalan folktale about Saint Narcisso of Girona. Legend has it that when the venerated man died, flies flew out of his tomb to attack the French invaders attempting to trudge across the Pyrenees mountains. A bust of Voltaire is also seen on one of the Venus’ drapes; this refers back to an earlier painting entitled Slave Market with the Disappearing Bust of Voltaire that was created in 1940. The brightly colored dots above the bull head oozing blood (which is supposed to be Islero) reference the emerging op art movement of the late 1960s/early 1970s. Cubism is also hinted at in the lower left hand corner in the fragmented, angular body of a floating Venus. Since most bullfights take place at 5 o’clock in the evening, Dali even painted the outline of the number “five” on the face of a pastel Venus on the left side. Finally, the last quirky detail that always entertains the viewers is the outline of a dog in the bottom center of the image. Composed of swirling, disembodied brown dots, the dog leaning over actually comes out of an earlier image called Cadaques (painted in 1923).

Overall, this painting, while rather busy and difficult to explain fully on a tour, is still a tour de force that summed up Dali’s prolific career. Even more interesting is the almost mythical life of Manolete, the doomed bullfighter that was the epitome of Spanish machismo and culture. Although he rests in Cordoba, Spain, his life and legacy still lives on in the halls of the Dali Museum and in the bodies of those beautiful Venus’ from antiquity.

Buy Barnaby Conrad’s book here.

Find out about “The Matador’s Mistress,” a movie made about Manolete in 2008 here. Penelope Cruz is in it!

Visit the website of the Cervantes Hotel, the lodging in Linares that Manolete stayed at.